In a recent interview on David Perell's podcast How I Write, Morgan Housel identifies one of the worst pieces of writing advice, though in reverse.

I asked Morgan Housel: "What's the worst piece of writing advice you hear?"

— David Perell (@david_perell) October 16, 2025

His response: "Know your reader." pic.twitter.com/3a2OYTopnd

"What's the single worst piece of writing advice that you often hear?" Perell asks Housel, a nonfiction writer known for making complex financial concepts accessible to everyday readers. Housel responds:

I think it's the very common, Know your reader.

Writers who think about their readers, according to Housel, spill too much ink on explanations. They would be much better off writing as though in "a diary for themselves."

"Just write for yourself," advises Housel, readers be damned. "Even if your reader doesn't know this thing," he says, "make them look it up... If they don't know it, that's their problem. They can just figure it out for themselves."

This kind of self-centeredness, I think, is at the root of all bad writing.

As it turns out, Housel agrees with me, at least in practice. For an inspection of his own writing shows a deep concern for the needs and interests of his readers, which may account for his phenomenal success as a nonfiction writer.

Nonfiction writers would do well to forget the adage Do as I say, not as I do. Instead, set aside the advice from one of our generation's most successful nonfiction writers, and Do as he does, not as he says.

Know Thy Reader

The trouble with knowing your reader, according to Housel, is that writers too easily conflate it with "pander to your reader."

Writers pander to their readers when they "explain" themselves "deeper" than readers find necessary.

Housel cites as evidence The Economist which, despite being "a well-written magazine" with "great prose," often uses superfluous subordinate clauses to define entities that its readers know well—e.g.:

"How many Economist readers don't know [Morgan Stanley]'s a bank?" exclaims a frustrated Housel. "You don't need to put that there."

Housel's frustration is understandable. Most readers find it tedious to slog through background information that doesn't account for their needs and interest. And nobody could object to his suggestion that writers be brief.

But Housel's diagnosis of the problem misses his own point.

Writers like those at The Economist, according to Housel, frustrate their readers when they ask themselves, "Who is reading this?... What do they want to hear?" But of course the opposite is true: It's precisely because the writer ignored those questions that Housel is frustrated. If the writer really had bothered to consider his reader, he would never have included such superfluous background information.

Housel's prescription—that writers should ignore readers altogether—is, in a roundabout way, the real answer to Perell's question.

And Housel's prescription—that writers should ignore readers altogether and simply write as though they were "writing a diary for themselves"—is, in a roundabout way, the real answer to Perell's question. While the diary as a genre is synonymous with solipsism, Housel argues that the impression it gives to writers that "no one is going to read this" turns them into "a good writer" who can "get to the point."

But it's when writers think that "someone is going to read this" that the trouble starts: they start to explain unfamiliar ideas and structure the piece in a way that, from one perspective, might suit the reading process but, from Housel's perspective, degrades the "good prose" of the diary entry.

Write with the Door Closed, Rewrite with the Door Open

Housel has a point. Just not the one he thinks he's making.

It's true that writers should keep readers out of mind in the early phases of a project. During this first phase, writers use writing as an extension of their own thinking. It's a messy, recursive process of discovery that Stephen King calls "writing with the door closed."

Writing advice from Stephen King:

— William Fitzpatrick (@WriterScience) February 2, 2025

Write with the door closed; re-write with the door open. pic.twitter.com/TmDQLxKQ6m

But it's not the case that this early writing is what many readers would consider "good prose." On the contrary, the writing that emerges in this early phase uses patterns that interfere with the reading process.

For just one example, consider what happens when you write nonfiction:

- you start off (at the top of the page) with a problem,

- you bring in some evidence and analysis (in the body),

- and you stop writing when you arrive at a solution (at the bottom).

Here's why most nonfiction writing falls flat: Writers and readers use writing differently.

— William Fitzpatrick (@WriterScience) October 18, 2025

Writers use writing to think about the world. We find problems, analyze evidence, and use our own reasoning to make sense of it all. That process is rarely neat and tidy; its patterns are… pic.twitter.com/J7XQ0T7c4w

Following Housel's advice, you have successfully written something valuable without concern for the reader's needs and interests, and after some light edits you hand this off to them. They read your document, searching for the value. They expect to find it up top, near the end of the beginning. But you've buried it in the bottom.

Readers need more than light edits. They need your text to be tailored to their needs and interests. Ignore these, and you'll put them into the position of the Economist's readers, frustrated at the writer who hasn't even bothered to consider the knowledge and expertise they bring to the text. This second phase of editing for specific readers is what King calls "Writing with the door open."

Expert Writing, in Theory and Practice

Fortunately, Housel doesn't actually believe what he says, which may account for his success as an author.

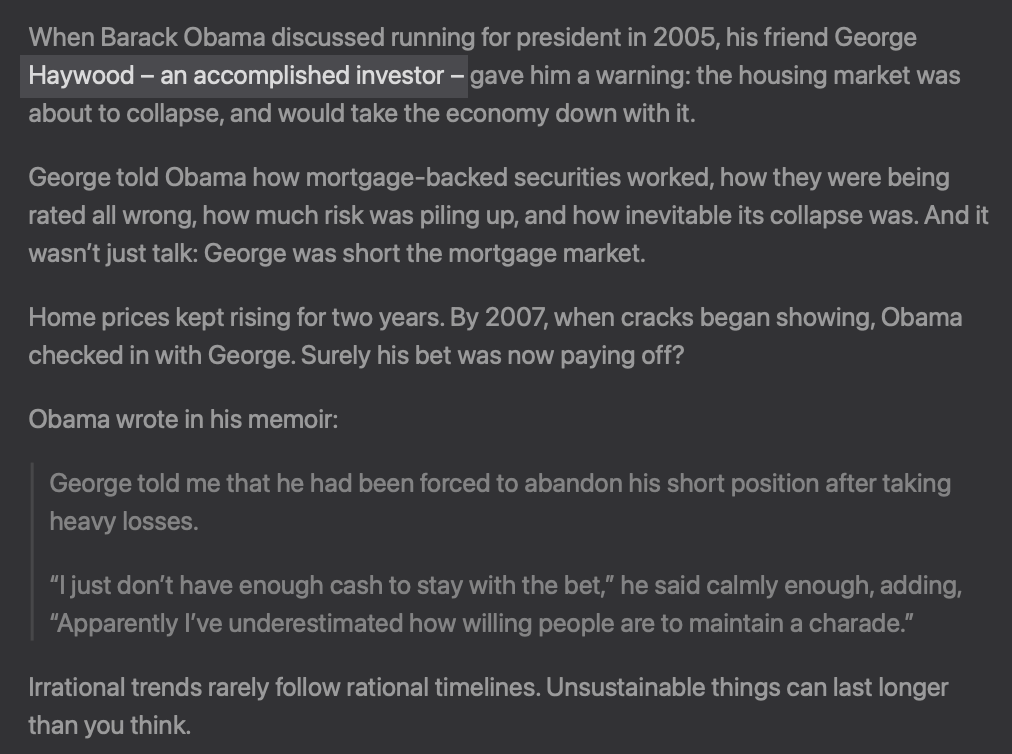

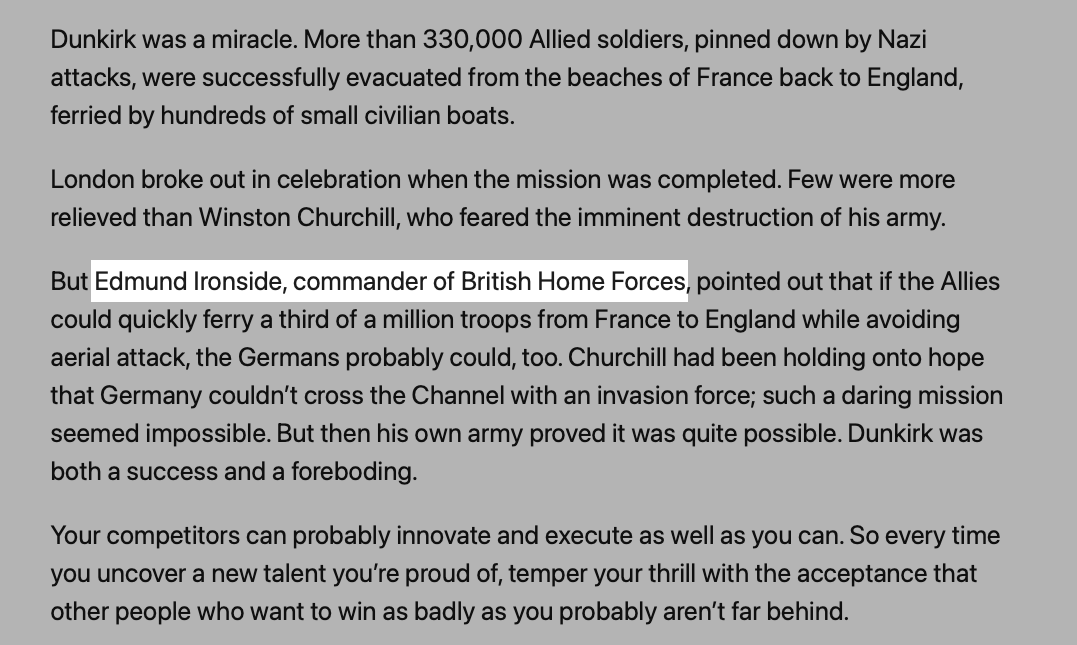

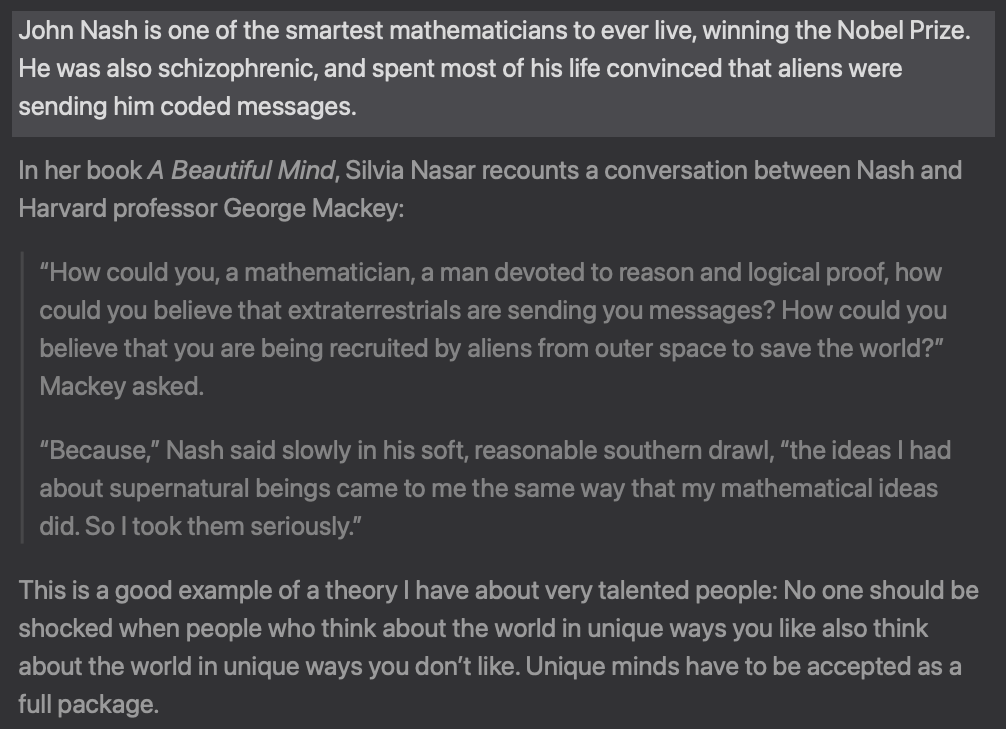

In the excerpts below, the author knows that readers are already familiar with Barack Obama, Winston Churchill, and the battle at Dunkirk, and that some may need help identifying George Haywood and Edmund Ironside.

He doesn't care that most of his readers already know about John Nash, which may frustrate some.

But what's certain is that Housel's writing is no diary entry. It's the product of a writer who cares deeply about his readers.

Excerpts from "A Few Short Stories" by Morgan Housel, a writer who carefully considers his readers

Planet Fiction

The idea that writers should shut readers out of their mind, I think, is an invasive species of writing advice from the world of fiction.

On planet fiction, readers willingly hand off the reins of their attention to the author, who has free license to do anything to readers except bore them. These writers are (and should be) free to pursue their interests without concern for audience.

But over on planet nonfiction, the writer-reader contract is different. Readers are choosey. They're not even readers, in a certain sense; they're more like prospects, who may trade their time and attention for your writing, but only upon perceiving its value. Until such a perception, they're just browsing.

Writers who ignore the needs and interests of specific readers simply do not get read.